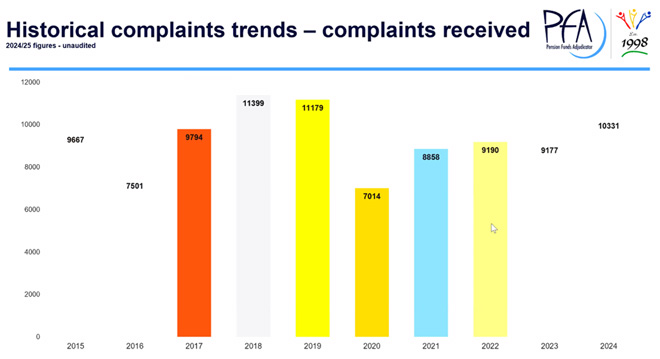

More than 10 000 complaints landed on the desk of the Office of the Pension Funds Adjudicator (OPFA) in 2024, with non-compliance by employers and withdrawal delays making up the lion’s share.

Together, section 13A compliance issues and disputes over withdrawal benefits account for over 83% of all complaints received during the 2024/25 financial year, according to Deputy Pension Funds Adjudicator Naheem Essop (pictured).

These two complaint categories have topped the list year-after-year since 2015, Essop told a webinar hosted by the Institute of Retirement Funds Africa on 13 May.

“Some complaints relate to delays in processing withdrawals or employer non-payment of contributions, only discovered when members attempt to claim their benefits upon exiting the fund,” he explained.

Section 13A of the Pension Funds Act (PFA) requires employers to pay over retirement contributions timeously and in full. But Essop noted that non-compliance remains endemic – and is often picked up only when a fund member exits employment.

The OPFA’s unaudited figures for 2024/25 show that section 13A compliance accounted for 44.33% of complaints, followed by withdrawal benefits at 38.80%. Other categories included death benefits (5.29%), section 14 transfers (3.58%), and two-pot system withdrawals (1.28%).

OPFA, which was established under the PFA, has a statutory mandate to resolve complaints lodged in terms of section 30A. It is overseen by the Ombud Council in terms of the Financial Sector Regulation Act.

Before the OPFA investigates a complaint, it must first be lodged with the fund. However, if a complainant hasn’t done so, the OPFA steps in to facilitate a direct resolution.

“Complainants must initially lodge their grievances with the fund, but where this hasn’t occurred, OPFA intervenes to assist in resolving issues directly between the complainant, fund, and employer,” said Essop.

So far in 2024/25, 711 complaints have been resolved through the OPFA’s “refer-to-fund” process – a step designed to mediate before a formal ruling is needed.

In addition, the Financial Services Tribunal (FST) plays a key role in reviewing decisions. “The FST may dismiss or remit determinations for reconsideration but cannot substitute its own decisions,” Essop said.

Out of 87 applications received during the year, 27 were remitted for reconsideration.

Essop said the increase in complaints is not surprising, given broader awareness among members and legislative changes such as the introduction of the two-pot retirement system.

“Since the Covid-19 pandemic, we’ve seen a steady increase in complaints, breaching the 10 000-mark in 2024,” he said. “From what we are seeing in the early part of 2025, it’s going to be a lot more.”

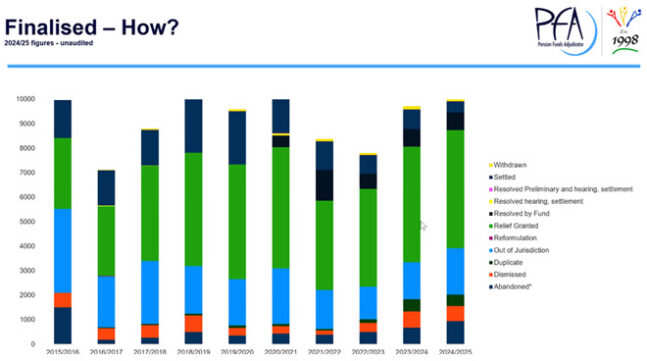

The OPFA aims to finalise 85% of complaints within six months – and according to the unaudited figures, it exceeded that target by resolving 93% of matters within 180 days.

Most outcomes result in relief being granted to the complainant, although cases may also be withdrawn, settled, dismissed, or found to be outside the OPFA’s jurisdiction.

The growing number of disputes is a warning sign for funds and employers to tighten compliance. For members, it highlights the importance of checking that contributions are up to date – before it’s too late.

Common issues when handling complaints

Retirement funds are failing to act swiftly enough when employers do not pay over member contributions – in direct contravention of legal requirements – and in some cases, this is leading to prescribed claims, the OPFA warned.

Essop said non-compliance with section 13A of the PPFA and the associated FSCA Conduct Standard 1 of 2022 (RF) is a persistent issue that undermines member protections and delays complaint resolutions.

Section 13A outlines the core requirement that participating employers must pay retirement fund contributions within seven days after month-end. The Conduct Standard builds on this by setting out the exact steps and timelines a fund must follow when an employer fails to pay or submit the required contribution schedules:

- Within 15 days of detecting the non-payment or missing schedule, the issue must be reported to the principal officer or the designated monitoring person.

- Within seven days thereafter, the board of the fund must be notified.

- Within 30 days thereafter, the issue must be brought to the attention of the affected member(s) and reported to the FSCA, along with a proposed course of action.

- If non-compliance persists for 90 days, the fund must report the matter to the South African Police Service within 14 days.

Essop emphasised that if these timeframes are followed, there should be no prescription – the legal expiry of a claim.

“But we often have to make orders where part of the contributions have prescribed, because the fund has done nothing for three years, notwithstanding that it has these duties that are in the FSCA Conduct Standard,” he said.

This inaction leads to knock-on problems, including delays in resolving complaints.

Essop said the OPFA frequently receives inaccurate information from funds, only to be sent revised submissions later, further delaying the process. “That causes delays because OPFA must then serve it on the other parties.”

In some cases, employers contest allegations of non-payment by producing contribution schedules and proof of payment, yet the fund fails to respond.

“So, you wonder, what is going on there at the fund, at the administration,” Essop remarked.

Communication failures between the fund and its administrator also appear to be a recurring issue. “There’s clearly a breakdown of communication between the fund and the administrator,” he said.

Adding to the confusion, Essop said the OPFA sometimes receives complaints lodged by funds that are too vague to act on.

“They lack clarity. You’re not really clear about what the fund is trying to claim from the employer.”

He reiterated that funds have a legal and an ethical responsibility to act when employers default on their contributions.

“It shouldn’t be left up to the member to fend for themselves when they are now exiting, and they realise that there is no money being paid to the fund on their behalf.”

Essop said such failures raise the possibility of holding fund trustees accountable.

“They do have legal duties to act. Like I said, there’s the FSCA Conduct Standard that says they must do things within a certain amount of time, and if it’s not happening and then a member exits, there is a question about whether they could ask us to hold the fund trustee liable for not complying with their legal duties.”

Death benefit decisions must be transparent and well-motivated

Retirement funds must provide clear reasons for how they allocate death benefits, or risk having their decisions reviewed by the OPFA

Essop said that in terms of section 37C of the PFA, funds are required to conduct a proper investigation into the circumstances of the deceased member, identify the legal and factual dependants, and make an equitable allocation of the death benefit. Importantly, they must also decide on the mode of payment.

The legal foundation for the OPFA’s oversight lies in the 2021 judgment in Swart N.O. and Others v Lukhaimane N.O. and Others, in which the High Court in Pretoria ruled that allocating a death benefit is an administrative action. This means the process must be both lawful and procedurally fair.

“Therefore, the fund’s reasons for their death benefit allocation must be transparent and given to the beneficiaries,” said Essop.

He added that trustees owe fiduciary duties to beneficiaries, as set out in section 7C(2)(f) of the Act. “Failure to provide reasons makes the decision reviewable.”

Essop said the OPFA frequently receives complaints from beneficiaries who do not understand why the fund awarded them a specific percentage of the death benefit or why others received more.

“Often, we get requests for extensions when responding to a death benefits complaint, and we do grant extensions, reasonable extensions. We’re not harsh about it, but I think when you do a death benefit allocation, your reasons and your trustee resolution, your investigation report, that should be readily available,” he said.

“There shouldn’t really be much for you to then go and scratch around for new reasons now, why you made the allocation that you made. You should be able to present that to us quite soon after we request your response.”

He also criticised funds that cite the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA) as a reason for withholding information, particularly when the underlying investigation appears inadequate.

“This often happens in cases where the investigation itself wasn’t done properly. And so, it seems like it’s an excuse to hide a poor investigation.”

Essop pointed out that POPIA includes exceptions for entities performing a public function.

“If you read POPIA, if there is a public entity performing a public function, POPIA doesn’t apply to that,” he said.

He advised funds to obtain consent from beneficiaries at the start of the investigation process.

“A practical way is for you to just seek consent at that stage, to say that whatever information you provide may be subject to the Pension Funds Adjudicator’s process or to the court, etc., and that the information will be shared, although it is by operation of law.”

Essop also clarified that where the OPFA sets aside a fund’s original decision and refers the matter back for reconsideration, the fund’s second decision remains subject to the Adjudicator’s scrutiny.

“We do have some issues there. But I think the correct position is that the second decision is subject to the OPFA process.”

Funds must act transparently when withholding benefits

Retirement funds must provide clear, timely justifications when withholding a member’s benefit under section 37D of the PFA – and cannot rely on post hoc evidence to defend their decisions.

Essop noted that, as with death benefits, funds have a duty to act with transparency and to afford members an opportunity to respond to allegations made by their employer.

According to section 37D, a fund may withhold a member’s benefit if the employer has instituted proceedings to recover damages caused by the member’s misconduct. However, as in the case of death benefit allocations, the fund must provide a proper report and clear reasons for its resolution, and these must be readily available when called upon.

“You do have to put the allegations as it was put by the employee. You’ve got to put it to the member for them to respond,” said Essop.

He cited the judgment in SA Metal Group (Pty) Ltd v Jeftha and others [2020] 1 BPLR 20 (WCC), which confirmed that a member must be given an opportunity to be heard before the fund makes a decision on withholding.

Essop emphasised that the fund’s decision must be capable of being justified at the time it was made.

“You shouldn’t then have to be afterwards, be bringing in other things to try and justify the decision, things that happened afterward, after your decision has been made.”

Inadequate procedures not only undermine fairness but expose funds to complaints, delays, and potential findings of maladministration by the OPFA. As with all administrative actions under the PFA, proper process and fairness remain paramount.