The collapse of a number of banks over the past week is reverberating across global financial markets. Although central bankers and other major banks acted swiftly in their bailouts, nobody knows how big the bank-driven financial contagion could turn out, but it does look like a Black Swan event (“rare events with serious consequences”, according to Nassim Taleb, author of The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable).

The flight to quality and security is already favouring government bonds in developed economies, while equity markets have slumped.

According to BCA Research, the economic fallout from the crisis will come through tighter lending standards and slower credit growth. Central bankers’ hands will be forced, as the United States and the Eurozone are facing recessionary conditions. They are likely to abandon quantitative tightening sooner than later, meaning that we are probably at or near the top of the interest rate cycle. The Fed and other central banks may even turn to quantitative easing later this year.

The banking crisis, as well as the slump in equity prices and listed property, could severely dent consumer and business confidence. Furthermore, Moonstone’s leading indicator, consisting of equity valuations and certain economic data, points to a contraction in US industrial production of about 3% to 4% in coming quarters.

A negative earnings surprise awaits

But what lies ahead for financial markets?

I agree with BlackRock’s assertion in a recent note that the consensus estimate for flat earnings in the S&P 500 for 2023 compared to the 2022 calendar year is too high. That was even before the current Black Swan event.

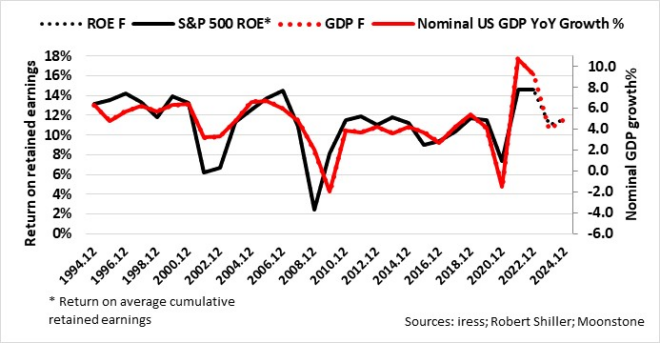

From a top-down point of view, the return on cumulative retained earnings (ROE) of the S&P 500 index historically had a strong relationship with year-on-year US GDP growth in nominal terms. Assuming that the most likely scenario for US GDP growth on the current calendar is 1% in real terms, with CPI inflation at 3%, nominal GDP growth will be 4% (growth in real terms plus inflation), compared to growth of more than 9% in 2022.

If the relationship between ROE and GDP growth holds, the ROE could fall to about 10% in 2023 from more than 14% in 2022. The drop in ROE equates to a fall of about 20% in earnings compared to 2022. Yes, a negative earnings surprise is awaiting the market.

Watch the froth

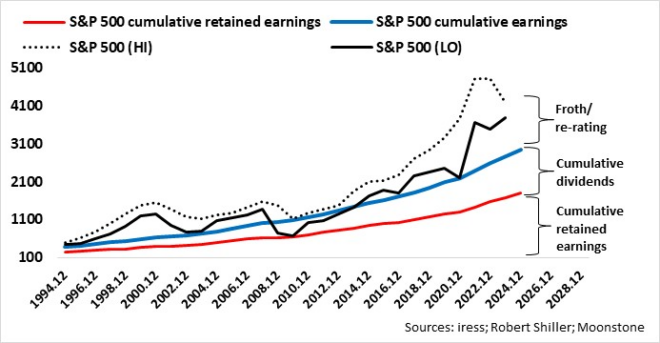

Earnings drive the value of a company. Profits or earnings of a company are distributed in two ways, namely dividends and retained earnings. Retained earnings are effectively invested by the company on behalf of its shareholders in the company’s assets or used to reduce liabilities. The net effect is an increase in shareholders’ interest or equity or net asset value, or a decrease in the case of losses.

Froth is described by Investopedia as “where asset prices become detached from their underlying intrinsic values as demand for those assets drives their prices to unsustainable levels”. This backdrop also applies to a portfolio of stocks or an equity index.

My top-down analysis indicates that over the past 37 years, the S&P 500 at some stage always tested the cumulative earnings level when equity markets came off the boil due to major events, such as Covid-19 recently. However, the sell-off of equities during the global financial crisis in 2008/9 was such that the S&P 500 index traded down to the accumulated retained earnings level or shareholders’ interest.

With the S&P 500 currently at 3892, the froth is about 40% and compares with the pre-2008 crash levels of about 46% and the pre-2000 crash levels of about 150%. Where the US equity markets go, the rest of the world, including South Africa, will follow by default.

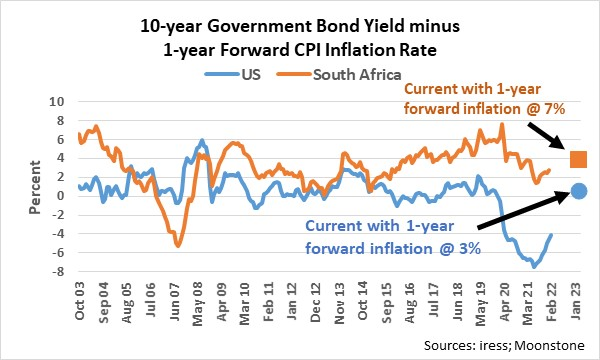

In contrast, it appears that despite the recent falls in government bond yields globally, there is little froth in the bond market. The US 10-year government bond yield adjusted for CPI inflation of 3% one year out is currently 0.6%, in line with the average of 1% from 2003 to 2019 (pre-Covid). The South Africa 10-year government bond yield adjusted for CPI inflation of 7% one year out is currently 3.9%, in line with the average of 3% from 2003 to 2019.

My preferred investment strategy

During previous Black Swan events, emerging-market currencies, specifically those of high-sovereign-risk countries such as South Africa, came under attack, which sometimes led to tighter monetary policies to stem capital outflows and fight inflation. The bond markets of high-risk countries tend to follow the trend of developed markets, though.

As a medium-risk, long-term investor, the mounting risks in global equity markets and the prospect of short-term interest rates peaking in coming months, together with the value proposition of global bonds, underscore my preferred investment strategy of 50% equities and 50% bonds. I hold cash for tactical purposes only.

In light of South Africa’s precarious situation, I doubt whether the yield spread between South African and US government bonds fully compensates for the risk, and I prefer a healthy balance between South African and global government bonds.

At this stage, it seems that the fallout from the banking crisis will not match that of the global financial crisis, but it could turn out to be very uncomfortable for equity investors and savers.

Ryk de Klerk is an independent investment analyst.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies. The views in this article do not constitute financial advice.