Izak Odendaal, Old Mutual Wealth investment strategist, shares his views on the outcome of the 54th annual gathering of the World Economic Forum (WEF), which took place from 15 to 19 January, in Davos, Switzerland.

The concept of globalisation has come under siege in recent years. The pandemic, wars, and domestic political pressures mean countries are moving away from free trade towards a greater focus on resilience and national security. This doesn’t mean globalisation is dead, as some claim, just that it is taking a different direction.

The International Monetary Fund calls it “slowbalisation”.

Either way, the mood in Davos was seemingly more focused on the risks facing the world economy, from conflict to climate change, than on opportunities for growth and expansion.

One silver lining: 2024 will be a year of falling, not rising, interest rates. We do not know yet how far or how fast they will fall – hence the market gyrations over the past two weeks – but lower borrowing costs reduce financial stress pretty much everywhere.

It was into this uncertain environment that a delegation of South African business and political leaders, including Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana, tried to sell the country at Davos as an investment destination. It has been tough going in recent years, as low growth and massive infrastructure challenges mean foreign businesses have not exactly been falling over their feet to invest here.

Losing competitiveness

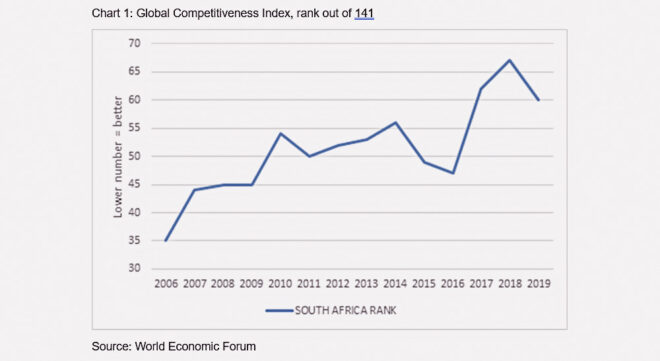

The WEF is not only an event; it is also a think-tank that publishes reports on key issues affecting the global economy. For several years, it published a flagship Global Competitiveness Report that assessed and ranked countries across 12 key pillars, including institutions, infrastructure, education, efficient labour markets, financial sophistication, market size, and innovation.

South Africa ranks highly for market size, business sophistication and financial market development; poorly for education and labour market efficiency; and in the middle of the pack for the rest.

It was ranked 60th overall out of 141 countries in 2019, the last year the report was published. It squeezed in between Greece and Turkey – ahead of the likes of Brazil, India, and Argentina – but behind China, Indonesia, and Mexico.

At the top of the list, as one might expect, was Singapore, the United States, Hong Kong, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. The bottom five were Mozambique, Haiti, Yemen, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Chad.

South Africa’s rank has declined over the years. In 2006, it was as high as 35.

Although Godongwana and company can emphasise important recent economic reforms, sceptical investors will point out that these changes have yet to arrest a long-term deterioration in competitiveness.

Portfolio investors

When we talk about “foreign investors”, it is worth differentiating between different categories. The most important distinction is between portfolio and direct investors.

The former buy South African stocks and bonds. Most of them are probably not even people, but algorithms.

They will assess whether South African stocks or bonds offer good value based on the country’s growth prospects, inflation outlook, political stability, and so on, and buy or sell accordingly. These decisions are greatly influenced by prevailing global market conditions and risk appetite, with South African assets typically benefiting from “risk-on” market regimes.

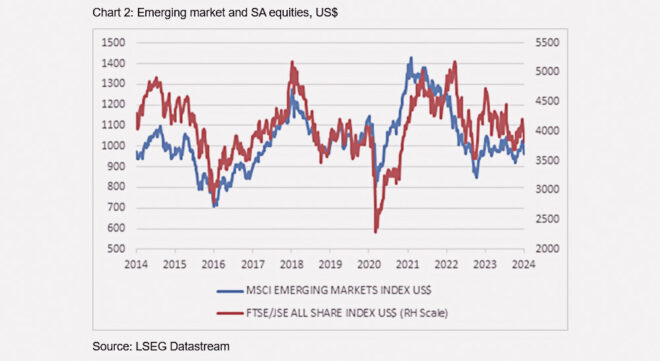

For instance, a widely shared recent Bloomberg article said the JSE experienced net selling by foreigners for the past eight straight years, totalling $53 billion. But this needs to be seen in the context of outflows across emerging markets, a strong US dollar, and lacklustre performance of emerging market equities over this period.

It is hard to know which is the chicken and which is the egg here. Outflows are probably a response to underperformance more than it is a cause.

Bond outflows have been less dramatic, but the foreign ownership share of government bonds has declined notably, from about 40% to 25%. As the government has issued more and more bonds, they have primarily been bought by local banks, retirement funds, and unit trusts (as income funds have gained in popularity).

Portfolio investments are important, because they are a source of hard currency, offsetting the country’s persistent current account deficit. The flipside is that substantial dividend and interest payments are made to foreigners every year. Beyond that, however, it doesn’t fundamentally matter whether a share is owned by a local or a foreigner.

Foreign direct investment

The other category of foreign investment is longer-term in nature and usually known as foreign direct investment or FDI. This is when an international company buys a South African firm or sets up operations here, such as building a factory or a mine or opening a call centre.

FDI brings capital and know-how into the economy and often stiches local producers into crucial international networks. It is therefore very important for long-term growth.

Since the upfront costs are usually substantial, these are investments that must pay off over many years, possibly decades. Companies need to have confidence that the operating environment will continue to be conducive many years into the future.

Broadly speaking, a foreign firm will invest in a developing country where one or more of the following conditions exist:

- Production costs (particularly wages) are lower than elsewhere, such that it can manufacture goods in the country to export into other markets.

- There is a large untapped or rapidly growing domestic market to sell into.

- There is a natural resource to exploit, such as an ore body or a tourist magnet.

- The country has a strategic location that can be used for trans-shipment or exporting into specific markets.

- There are specific policy incentives, such as tax-breaks or Special Economic Zones that make otherwise unpromising investments lucrative.

- There are profitable or cheap existing businesses to acquire.

China is perhaps the best example of the first two categories. It has long been a major recipient of FDI, initially because it was an exceptionally low-cost producer, becoming the world’s factory in a few years after joining the World Trade Organization in 2001.

It made heavy use of Special Economic Zones to lure foreign manufacturers. But as the country industrialised and wages rose, global firms increasingly salivated over its massive and rapidly growing consumer market. Something similar is happening in India.

Today, China is no longer the cheapest place to produce, and countries such as Vietnam and Bangladesh are soaking up FDI. Companies are also deliberately diversifying supply chains away from China, while policy uncertainty has increased. As a result, FDI into China has slumped.

FDI and South Africa

The South African economy is growing very slowly, so the consumer market is not growing rapidly. Moreover, it is well served by local firms, including local firms that bring big-name global brands here.

As a production base, South Africa suffers from the so-called middle-income trap. Wage levels are too high to compete with low-wage countries on cost, particularly in Asia, while skills levels are too low to compete head-on with Europe and North America.

We used to have cheap and reliable electricity as a competitive advantage, but those days are long gone. Moreover, apart from loadshedding, the fact that most of our electricity is produced by burning coal is increasingly a problem as the global emphasis on greenhouse gas emissions intensifies.

The European Union will implement its so-called Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism in 2026, which effectively taxes imports that are produced with “dirty power”. Although the details are still being finalised, this is a threat to any South African-based producer exporting to Europe.

South Africa’s massive potential as a tourism destination is similarly threatened if travellers in rich countries shun long-haul flights to shrink their carbon footprints.

Crime is another major turn-off for potential tourists. In fact, crime is increasingly a major issue for business leaders across sectors, particularly mining, construction, and transport.

Singapore and Dubai are classic cases of countries exploiting a strategic location to attract substantial FDI. Since the 1994 free-trade agreement with the US and Canada, and increasingly in recent years, Mexico is also benefiting from its neighbourhood.

South Africa, meanwhile, has always liked to position itself as strategically located to act as the “Gateway to Africa”, a springboard for global firms into the rest of the continent. Certainly, the strength of our financial and business service sectors makes us a top contender for this role. But a gateway requires strong logistical links, which is increasingly not the case. Instead, we see some South African businesses turning to the neighbouring Maputo port because of congestion at Durban.

Moreover, countries such as Nigeria, Morocco, and Kenya are also keen to be seen as gateways.

As for natural resources, these are scattered all over the globe, but some countries are better at attracting investors than others. Despite its sizable resource endowment, South Africa has struggled because of electricity and transport bottlenecks, an onerous and inefficient licensing regime, and uncertainty that the regulatory goalposts won’t shift.

It is the final category of FDI that South Africa continues to do relatively well. Several well-known South African businesses have been acquired over the years, including Distell, which was recently bought by Heineken, and Pioneer Foods, which was bought by PepsiCo. Although this type of FDI does mean foreign capital and know-how flow into the country, it does not necessarily translate into faster economic growth if these firms focus on market share and profitability and not growth.

Existing South African companies are often attractive because they have very strong competitive positions. In these cases, it is much easier to buy an existing firm than start and grow a rival. Moreover, the local firms are attractive because they are cheap, typically trading on low price-to-earnings multiples on the JSE. Direct investors are stepping in (here and there) because portfolio investors have not been interested.

Despite all the above, South Africa still attracted $9 billion in FDI in 2022, according to UN data, a slightly higher amount than prior years.

Risk and return

So how should the South African delegation at Davos have sold the country? Remember that both direct and portfolio investors ultimately care about risk-adjusted return, although the nature of risk and return is obviously different in each case.

Reduce the risks and increase the potential return, and the money should start flowing.

The risks can primarily be reduced through reducing the regulatory burden and increasing regulatory certainty, lowering the cost of doing business, and getting a grip on organised crime. Macroeconomic stability – manageable levels of government debt, low and stable inflation, and a less volatile exchange rate – is also important.

On the returns side, the big opportunities in the FDI space lie in the fact that the country has a massive infrastructure backlog that can only be cleared with private capital and management skills.

Infrastructure is a growing asset class internationally because of its steady return profile, and there are big established players looking for opportunities. BlackRock, the world’s largest asset management company, announced a splashy $12bn acquisition of Global Infrastructure Partners earlier this month.

The problem in South Africa is that infrastructure has tended to be monopolised by the state, roads, rail, ports, dams, and power stations. This is changing. The government’s policy is shifting, belatedly and out of necessity, towards private participation. “Privatisation” is still a swear word in some circles, but in practice, there is little difference between selling an asset and granting a 25-year concession to upgrade and run it.

To be clear, the private sector cannot solve all infrastructural challenges. It will only invest in infrastructure where there is a return to be made. This means tolled highways, ports, railways, power plants, airports, and so on, but not rural or suburban roads, for instance. For the latter, we will still need to rely on the government, particularly local government.

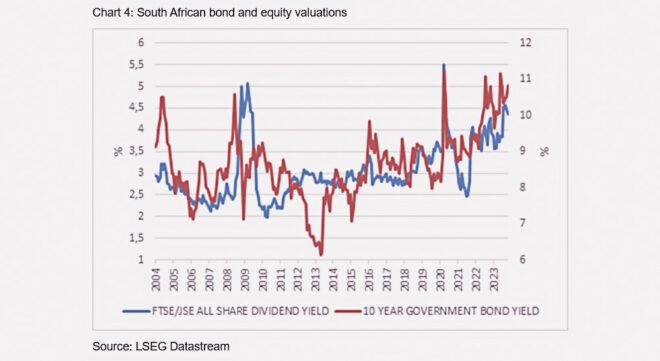

For portfolio investors, the opportunities lie in undervalued bonds, equities, and currency. The latter is particularly important, because a stock-standard 10% move in the rand can wipe out the annual rand return from a bond for a foreign investor. They can hedge this, of course, but it is expensive with high local short-term interest rates. Therefore, expect inflows to pick up once investors sense tailwinds building behind the rand, including a weaker US dollar.

In other words, although South Africa has much to do to get its own house in order, firmer capital inflows would also require a more conducive global environment. This is not something it can influence, but perhaps the big shots at Davos can.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies. The information in this article does not constitute estate or financial planning advice that is appropriate for every individual’s needs and circumstances.