Succession planning for independent financial adviser (IFA) firms is a topic that frequently triggers lively debate and commentary at industry events. The debate has centred on which succession model is the best, the need for consolidation of smaller IFA firms facing cost pressures, practical considerations for different succession models, and valuing an IFA firm.

The FSCA has also expressed a keen interest in adviser succession and requires advisers to have a formal succession plan to ensure continuity of services to the firm’s clients.

In this article, Jaco van Tonder, the head of Adviser Services in South Africa at Ninety One, shares some of the most common themes in the asset manager’s discussions with South African advisers about succession planning.

Adviser M&A and succession planning – two sides of the same coin

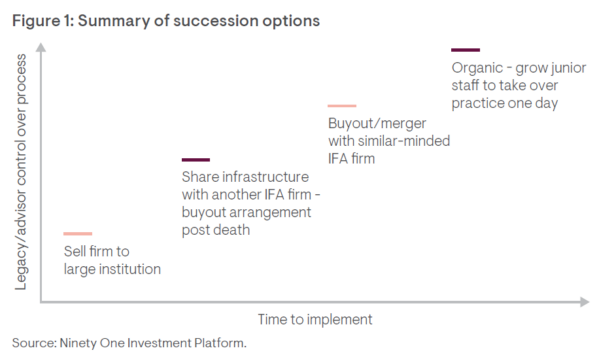

Our first learning is that a discussion about the mergers and acquisitions (M&A) of advice firms is in essence a succession planning conversation. In fact, we often use the following graphic to illustrate this point:

In talking to advisers about these succession options, the learning was that they represent some type of M&A transaction in their business, because all succession plans eventually result in a change of ownership in the IFA firm. Even in the case of organic succession, the internal junior adviser taking over the firm must eventually buy out the founder.

The next key takeaway is that two main factors drive the different succession options, as highlighted in Figure 1:

- Succession varies in terms of the time it takes to implement. Selling your business to a large corporate can be done in under 12 months, whereas an organic succession plan generally takes more than 10 years to pull off successfully.

- After the sale of the business, the adviser’s control over the outcome is the other important driver. Where there is organic succession, the founder adviser remains in control until they retire. However, when a large financial firm buys a smaller IFA firm, the smaller firm loses most of its independent decision-making once the deal is inked.

Many advisers who have been through the process of implementing one of these succession models admit to underestimating one of these two factors. They either underestimated how long it would take to implement the plan or they underestimated the extent to which they would lose control over many aspects of their own business after the transaction.

Advisers retire much later than they realise

A second topic that often causes strain after the implementation of a succession plan is when financial advisers really retire.

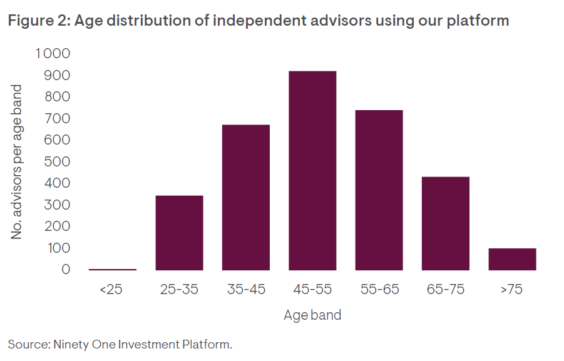

Figure 2, which provides a summary of about 3 200 active IFAs dealing with the Ninety One Investment Platform, is a good starting point.

Most advisers remain active up to at least age 65, maintaining a sizeable client load. Furthermore, a significant proportion of advisers continue working beyond age 65. It is only at age 75 that most advisers appear to give up practising.

The key conclusion here is that those involved in crafting succession plans should make provision for the selling adviser to work until at least age 65. There is a good chance that the selling adviser will continue working beyond age 65 but with a reduced client load. Many a well-intentioned succession plan experiences strain because the selling adviser wants to continue working after their intended retirement date, whereas the buyer would like them to retire.

Founding advisers often do not provide for their retirement

It might seem strange that a financial planner neglects their own personal retirement plan, but it happens more frequently than you would expect. Quite often, a founder adviser ends up at age 60 with limited financial provision outside of their advice practice.

These succession plans are notoriously tricky to pull off because the selling adviser needs a very high valuation on the deal to fund their own retirement. This has been the experience of several advisers looking to sell their firms to fund their retirement.

We estimate that an adviser can replace only 50% of the earnings from running their own advice practice if they sell the practice for cash and live off the proceeds (based on a typical sale valuation – outlined in the next section). Normally, this is not enough, and advisers who find themselves in this position are often forced to continue working for the buying firm after the acquisition. This has big implications for the buyer of the practice.

There is no single ‘correct’ valuation for an advice business

When engaging with advisers on their succession plan, the conversation invariably leads to a discussion on what an advice business is worth. Entire articles have been written about valuing an advice business. This is particularly the case in the United States and the United Kingdom, which have seen aggressive consolidation of advice firms by private equity-funded consolidator networks.

Resisting the temptation to fall down the rabbit hole of discounted cash-flow valuation models, we would like to make the following broad observations based on recent engagements with many buying and selling advisers in the South African market:

- When an adviser sells their investment advice firm to another adviser for cash, and the firm is managed very similarly (with similar services and revenue lines) before and after the sale, the valuation generally ends up being in the range of 2.25 to 2.5 times the annual gross revenue of the business.

- If the practice is sold to a larger financial group, where the objective is to convert the clients of the selling firm into the buyers’ own financial products (generating additional revenue for the buyer), the valuation is generally higher. In these cases, it can exceed three times the annual gross revenue of the business.

- If the objective of the transaction is to facilitate an organic succession plan, where a younger successor in the practice acquires their first meaningful stake in the business, the valuations are generally lower. In these cases, valuations can be anywhere from one to two times annual gross revenue.

The key takeaway is that there is no single “correct” valuation of an advice practice, and the price varies significantly depending on the objectives of the participants.

Don’t overlook negotiating the other important issues

Our final theme covers “softer” issues, such as unhappiness with the culture of the new entity after an acquisition. The challenge of a cultural mismatch is often mentioned in IFA mergers and acquisitions in markets such as the UK and the US (markets with high adviser M&A activity).

There are several articles providing firsthand accounts of actual cases where deals failed a few years after conclusion. For those interested to read more about these international experiences, a good reference point is an article recently published on kitces.com by US-based blogger Bob Veres. In this instructive article, Veres relays the experiences of various adviser M&A transactions, where the deal created tension for reasons other than money. Many of these experiences resonate with what we hear from South African advisers.

Consider the following tips to avoid some of these unfortunate outcomes in your succession transaction:

- Spend enough time during the initial negotiation to agree how the “divorce” will happen if the deal fails for any reason. Ensure this is documented in the sale agreement.

- Investigate the operational and technology infrastructure implications of the sale and the disruption it will cause to your clients and staff.

- If you have never worked for a large corporate before, and you are considering selling to one, obtain as much information as possible about the cultural differences and how they might affect your staff and clients. Speak to other advisers who moved from running their own business to working for a larger corporate.

- Be clear about the investment philosophy and process and the client fee strategy of the buyer and how this will impact your clients.

- Have a full understanding of the future business focus of the buyer – particularly the balance between new business and assets under management growth on the one side, and client service and relationships on the other.

- Be clear about the employment future for your staff and what happens to them after the sale.

Adviser succession and M&A – its Siamese twin – are critically important discussions for the South African IFA market. A successful succession or M&A deal requires structured planning and negotiation – and most importantly, an adviser needs to devote sufficient time to navigate this multi-layered process prudently.

This article was originally published by Ninety One and republished here (with edits) by permission.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies. The information in this article does not constitute financial planning, business planning, or legal advice that is appropriate to every individual’s needs and circumstances.