The end of an era approaches. Warren Buffett, probably the greatest ever investor, will retire at the end of this year. He is certainly the world’s richest investor, with a net worth of about $160 billion, after already giving away much of his fortune.

Buffett has been at the helm of Berkshire Hathaway for 60 years, turning it into one of the most valuable companies in the world.

Apart from his unparalleled business acumen, his folksy Midwestern demeanour, modest lifestyle, and endless supply of wisdom endeared him to millions around the globe. Known to many as the Oracle of Omaha, referring to his Nebraska hometown, he is something of a cross between a corporate titan, philosopher, storyteller, and rockstar. Some 40,000 people flocked to Berkshire Hathaway’s annual shareholder meeting on 3 May to hear him speak.

At a time of tremendous global uncertainty, there are a few key take-outs from Buffett’s incredible career: the how, when, where, and why.

One and only

There are two important caveats upfront.

First, there is and can only be one Warren Buffett, a uniquely gifted and determined individual.

Buffett was born in 1930, the son of a US Congressman from Nebraska. As a child, he displayed a strong entrepreneurial spirit, getting involved in various small business ventures around the neighbourhood and working part-time jobs. He started investing when still a teenager, and his high school yearbook noted that he “likes math; a future stockbroker”. He filed his first tax return at 14!

The other reason Buffett’s success won’t be repeated is that he started his career at a particular moment in history, when markets were far more inefficient, and information was scarce. The entire investment industry has professionalised and expanded over the years and is hyper-competitive today. Information has become abundant, but attention is scarce. Buffett’s investment approach has been analysed to the nth degree and copied.

The way companies are run has also changed, with a far greater emphasis on shareholder returns from the 1970s onwards.

The second caveat is that although Buffett started as a portfolio manager, he cannot be compared with the fund managers whose names you will see on fact sheets today.

His success was turbocharged when he acquired Berkshire Hathaway, a struggling textile manufacturer, in 1965 and turned it into a holding company for his investments. In other words, it is not a fund.

And unlike a typical fund manager who faces liquidity, size, and other mandate constraints, Berkshire enjoys tremendous flexibility. (None of this should be construed as a recommendation to purchase or sell its shares – past performance is not a guarantee of future performance.)

Early on, Berkshire purchased insurance companies that generated cash to finance further acquisitions. Insurance companies collect monthly premiums, creating a steady “float” of cash (as Buffett called it) that could be used for acquisitions. Some of these were whole companies, and some were stakes in listed or unlisted firms.

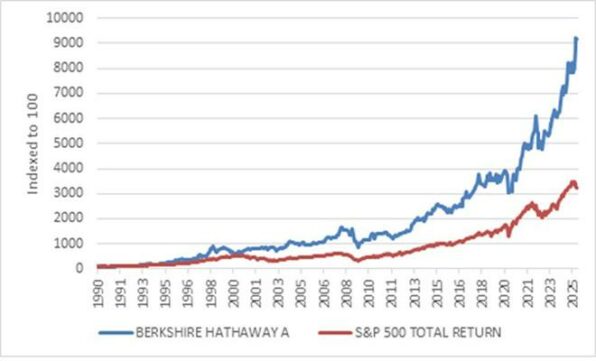

The net result is that, over the decades, Berkshire comfortably outperformed the S&P 500. However, there were periods of short-term underperformance. Even the most successful strategies will struggle at times, so this is an important reminder to stick to the plan.

Chart 1 | No contest: Berkshire versus the market

Source: LSEG Datastream

How: Price is what you pay, value is what you get

Buffett is a follower of Benjamin Graham, the so-called father of value investing, and worked for Graham’s investment partnership for a while.

Graham popularised the idea that investors should analyse the companies in which they were about to invest, to understand the financials, operations, and future prospects. When a company’s share price falls below its assessed intrinsic value, investors would have a margin of safety to purchase the share. This stands in contrast to the more speculative approach of buying shares in the belief that recent positive price momentum will continue.

Graham started his career in the 1930s, in the wake of the 1929 crash that wiped out the speculators but offered fantastic opportunities for value investors. All of this seems obvious now but was revolutionary at the time and laid the foundation for financial analysis as a profession.

Buffett’s approach evolved. Initially, he looked for cheap value shares or “cigar butt” companies, so-called because investors had thrown them away, believing them to be worthless, but there was still a puff left.

Over time, he shifted his focus towards the quality of the company, arguing that a good company at a reasonable price is a better purchase than a bad company at a massive discount, as long as the former has margin of safety.

Notably, Buffett bought a stake in Apple in 2016 when it was already one of the biggest companies in the world and no one’s idea of a “value” stock. It has been the most successful purchase in terms of the dollar amount of wealth created for Berkshire.

What has been consistent throughout, however, is that Buffett bought into companies, whether they were listed or unlisted, and whether his ownership was partial or total. He viewed these investments as businesses, not as financial instruments.

This approach might seem old fashioned to many investors these days, because modern finance often views equity investing through the lens of factors and correlations to the market and to one another, and less as businesses. Stock picking is increasingly seen as an unnecessary cost, because anyone can get the market return by buying cheap index funds. Buffett himself regularly encourages people to buy low-cost index funds and avoid the fancy stuff.

Nonetheless, at a time of great volatility and uncertainty on global markets, it is useful to remind ourselves that equity investing is still fundamentally about owning a slice of a company that entitles you to a share of its profits. It is the underlying profits that generate the wealth for the investor over time, although investors often obsess over short-term price movements. This is true whether you own shares directly, through funds or in exchange traded funds.

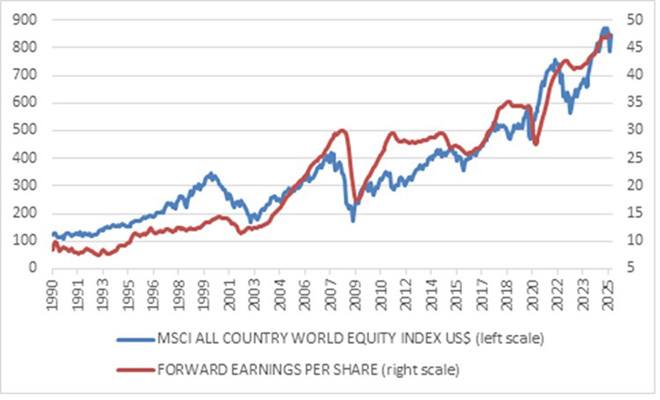

As Graham famously put it: “In the short term, the market is a voting machine, but in the long term it is a weighing machine.” Share prices are moved by sentiment in the short term, but over the long term, share prices follow earnings.

Chart 2 | Price follows earnings

Source: LSEG Datastream

Sometimes, share prices will be too high relative to future profit expectations, and sometimes too low. It is in these periods of mispricing where opportunities for stock picking and asset allocation lie.

Currently, Berkshire has a record cash pile on its balance sheet, some $350bn. Buffett and his team are in no hurry to deploy this and are seemingly waiting for opportunities to emerge. It is indicative of a pricey US market. The S&P 500 trades at 20x forward earnings, while unlisted companies also have elevated valuations given the abundance of private equity money floating around.

When: As long as possible

In his 1988 letter to shareholders, Buffett noted that “when we own portions of outstanding businesses with outstanding managements, our favourite holding period is forever”. This is one of his most famous quotes.

Of course, he does not literally mean “forever”. Berkshire has disposed of many acquisitions over the years, including ones that performed badly. After all, the industry dynamics do change over time, and Buffett has also made mistakes here and there. Everyone does.

But the belief in holding on to a good investment, being patient, and letting it compound is core to Buffett’s success. Although he is clearly an expert analyst of businesses and benefited from the Berkshire’s financial muscle (and his own reputation and network) to make attractive acquisitions, his real secret is arguably the patience to let investments compound. Albert Einstein never called compound growth the eighth wonder of the world, but he might as well have.

For instance, Berkshire took a 7% stake in Coca-Cola in 1988 that it still holds, as with the share in American Express it bought in 1991. In the 2023 annual shareholder letter, Buffett referred to it as “our own Rip van Winkle slumber that has now lasted well over two decades. Both companies again rewarded our inaction last year by increasing their earnings and dividends. Indeed, our share of AMEX earnings in 2023 considerably exceeded the $1.3bn cost of our long-ago purchase.”

Buffett’s personal fortune also benefited from the power of compounding. Buffett first became a billionaire in 1985, when he was 55 years old, according to Forbes. In other words, it took 20 years from acquiring Berkshire to make his first billion. Twenty years later, his net worth was $44bn. A further two decades on, and it has almost quadrupled again.

Where: Born in the USA

In his 2021 annual shareholder letter, Buffett wrote that despite “some severe interruptions, our country’s economic progress has been breathtaking. Our unwavering conclusion: never bet against America.”

He noted that nowhere on Earth has there ever been a better place for “unleashing human potential” like the US. He’s not wrong. The world has never seen a better machine for wealth creation than the American economy, although of course it has a dark side too (and Buffett has frequently spoken out against inequality).

He once noted that the luckiest day in his life was the day he was born, since he was born American, a white American male to be precise, as he has highlighted. This gave him opportunities available to less than 2% of the world’s population.

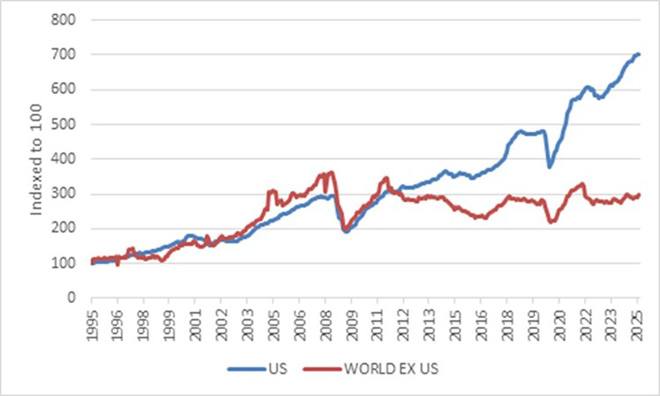

Chart 3 | American exceptionalism: earnings per share ($)

Source: LSEG Datastream

Most of Berkshire’s investments have been in American companies, and this continues to this day. American companies tend to be more shareholder-friendly, and it shows in terms of long-term profitability.

Of course, big questions are being asked about the US, its political economy, and its place in the world, which President Donald Trump is determined to remake.

The past two weeks have given investors optimism that Trump will sign trade deals and step back from the extreme tariffs he announced on 2 April. This is positive but does little to shore up faith in the notion that has prevailed for 80 years that the US is the bedrock of the global economy and financial system and a source of stability and predictable policies.

Many seem to take pleasure in this, but we will all benefit from a prosperous, innovative, and open America. Those who bet against America do so at their own peril.

However, betting against the US is not the same as reducing your allocation to a sensible level. Over the past decade or so, many global investors became overexposed to the US, driving up the value of the dollar in the process. This can continue reversing.

The why

Finally, the why. Why Buffett became so successful is because of immense determination, ambition, talent, and luck. But a multibillionaire who keeps working to the age of 94 also deeply loves what he does. This is an example to all of us, whether our profession is finance or anything else, that we tend to do our jobs better when we find work emotionally and intellectually rewarding, and if there is a purpose to what we do.

“Why” is also an important question every investor should ask themselves. Many people arrive at a financial adviser’s office and ask, “Where should I invest?” But it is the “why” that will ultimately determine the correct investment strategy: Why am I investing this money? What do I want to achieve with it?

Hopefully, a deeper understanding of the “why” will also motivate the investor to stick to the strategy and enjoy long-term success.

Izak Odendaal is Old Mutual Wealth’s chief investment strategist.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies.