Legal documentation can rarely be described as an edge-of-your-seat read, but the employment equity draft regulations published in February contain some surprising twists and turns, including an apparent “sunset clause” for affirmative action.

On 1 February, the Minister of Employment and Labour, Thembelani Nxesi, published for comment the draft regulations on the proposed sectoral numerical targets contemplated in section 15A of the Employment Equity Act (EEA).

This section was introduced by the amendments signed into law by President Cyril Ramaphosa on 6 April last year. They are still to come into effect.

Section 15A introduced sectoral numerical targets to ensure the equitable representation of people from designated groups (historically disadvantaged groups of people based on race, gender, and disability) at all occupational levels in the workforce. The amendment was set to empower the minister to identify national economic sectors for the purpose of the administration of the EEA and set numerical targets for each of these sectors.

On 12 May 2023, the minister published the draft five-year sectoral numerical targets for the identified national economic sectors.

The numerical targets focused on top and senior management, as well as professionally qualified and skilled levels and people with disabilities “where there is an underrepresentation in relation to the economically active population (EAP)”.

The EAP refers to the demographic composition of individuals – disaggregated by various demographic characteristics, such as race, gender, and disability status – who are actively engaged in the labour market, including those who are employed, unemployed, or seeking employment.

The targets were tabulated according to economic sector based on race (for example, African, coloured, Indian, and white) and gender, with national and provincial percentages indicated.

Separate targets were outlined for each of these racial and gender categories. The category “black” included African, coloured, and Indian persons.

The national targets were to apply to designated employers operating nationally, while the respective provincial targets were to apply to employers operating in the relevant province.

A designated employer would not be allowed to apply both the national targets and the provincial targets.

What followed was a whirlwind of public comment and debate; and the subsequent settlement agreement regarding the application of the EEA signed between the government and trade union Solidarity in June last year.

Read: Government and Solidarity sign agreement on employment equity

The settlement agreement was made an order of court in October 2023.

How the 2024 draft regulations compare to the 2023 regulations

According to Imraan Mahomed, director: employment law at CDH, there are essentially five broad elements in the 2024 draft regulations that have remained unchanged from the previous one.

- The number of economic sectors listed (18).

- The national targets.

- The fact that the five-year sectoral numerical targets solely focus on top and senior management, as well as professionally qualified and skilled levels and people with disabilities “where there is an underrepresentation in relation to the economically active population (EAP)”.

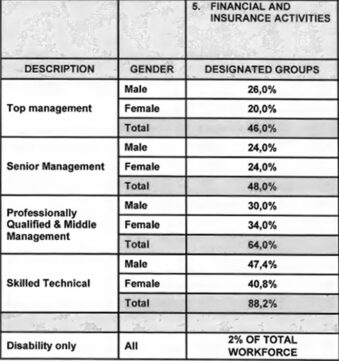

- The sectoral targets, except those for the financing insurance sector (see the table below).

- Employers will still be required to set numerical targets and goals for semi-skilled and unskilled occupational levels on their own – there’s no sectoral target for that.

The revised definition of “designated employer”, which now excludes those with fewer than 50 employees, also remained unchanged in the 2024 draft regulations.

According to an article published on law firm Bowmans’ website, the most significant changes, when it comes to the actual targets, are:

- There are no longer separate targets prescribed nationally and per province for each occupational level in a sector.

- In respect of each occupational level, there is now a single target for each sector, differentiating only between males and females.

Those targets apply to designated groups generally and are no longer broken down further per population group.

Werksmans Attorneys further clarifies that while designated employers will still be measured against annual targets set in reaching the five-year sectoral numerical targets, these targets will now be combined for designated groups per sector (in other words, they do not specify for African, coloured, Indian, and white), while providing specific targets for each gender.

“This does not mean, however, that designated employers are not still required to set targets in other occupational levels (semi-skilled and unskilled) as required by the applicable provisions of the EEA,” Werksmans says.

Hugo Pienaar, sector head, director: employment law at CDH, adds that while the distinction on racial grounds has been scrapped, employers still need to take into consideration the EAP.

“And that should be reflected at all levels in categories,” says Pienaar.

The new version also introduces the concept that an employer “may” (instead of “shall”) choose whether to use national EAP or provincial EAP targets.

Pienaar says the concept brings about a possible Constitutional Court challenge with regards to the extent to which employers should do so.

“And more so because of the provisions of the Act, which states provincial and national. We’ll have to see how that will play out,” he says.

What is “really new”, Pienaar says, is that when the 2024 draft regulations speak of affirmative action, it states that it is of a temporary nature. The language used, however, does not imply that there is a specific end date.

“There was no sunset clause when the Act was introduced, but when you look at local and international legislation, you comprise that when you’ve reached your targets, you can ‘park’ it for a while,” he says.

Another significant change is that the new version introduces a new test that talks about “justifiable/reasonable” grounds for non-compliance. Werksmans describes it as “a non-exhaustive list of factors that may constitute justifiable/reasonable grounds for non-compliance”.

Pienaar says “justifiable” wasn’t previously regulated and it may bring about a new emphasis.

“It’s almost like you want to bring in common law in an equity test, and one will see how that will play out. But it is a new ground, strictly speaking, that was introduced that will impact, ultimately, whether there will be fines imposed or not,” he says.

Five-year sectoral targets

The 2024 draft regulations contain an explanation on how the proposed five-year targets were determined and provide more detailed guidance for designated employers on how the targets are to be applied.

Bowmans says that, in this regard, the 2024 draft regulations indicate that, in setting the numerical targets, the Department of Employment and Labour (DoEL) took into account not only the demographic profile of the national and regional/provincial EAP, but also the workforce profiles of each economic sector, based on information provided in the 2022 EE reports submitted by employers to the DoEL.

“It takes into account the realities of a particular sector, which, for example, could be more dominated by males. In addition, unique sector dynamics such as skills availability, economic and market forces, and ownership, which were factors raised by stakeholders as part of the previous consultation process, have also been taken into account,” Bowmans says.

When it comes to applying the targets, the 2024 draft regulations now make it clear, among other things, that designated employers will be required to set annual numerical goals and will be measured against these annual goals towards meeting the relevant five-year sectoral targets.

“When setting these annual goals, designated employers must also take into account their workforce profiles and the applicable EAP,” Bowmans says.

National EAP vs provincial EAP

According to Werksmans, the national EAP shall apply to designated employers conducting their business or operations nationally, and the respective provincial EAP shall apply to designated employers conducting their business or operations provincially.

“While a designated employer can choose whether to use a national EAP or a provincial EAP, the designated employer cannot use national and provincial EAP at the same time,” Werkmans says.

The 2024 draft regulations now explain which EAP a designated employer should choose if it operates in more than one province, which was unclear from the May 2023 Regulations.

Bowmans says that, in these circumstances, the guidance indicates that a designated employer may choose the EAP of the province in which most employees perform their functions.

“Similarly, where a designated employer operates in more than one sector, it should choose the economic sector with the majority of employees,” Bowmans says.

What remains unclear is to what extent an employer has the discretion to choose between national and provincial.

Mohamed says it is not an open discussion, in the sense that an employer gets to choose one or the other. He says if you are a national business, you must use the national EAP.

He says when you refer to “discretion”, it applies to provincial. But, he says, there aren’t specifics to the provincial EAP in the 2024 draft regulations.

“How do you apply a provincial target when there’s no reference to it? So, what is the employee then supposed to be doing? Because the reading, currently, on regulation seems to be a suggestion of the national targets,” says Mohamed.

Affirmative action

Another new addition is that the 2024 draft regulations restate some of the key principles relating to the implementation of affirmative action measures, in line with the EEA and as interpreted by South Africa’s courts.

This content (found in Regulation 4) comes directly from the Solidarity settlement agreement, which was to be gazetted “as part of the 2023 Employment Equity Regulations”.

Werksmans said the 2024 draft regulations emphasises that no absolute barrier may be placed on any employment practices.

“In addition, no employer will incur penalties or any form of disadvantage if in the compliance analysis of affirmative action in any workplace there are justifiable/reasonable grounds for non-compliance. Furthermore, an employee’s employment cannot be affected as a consequence of affirmative action,” Werksmans says.

Legal conundrums

Once the amendments to the EEA are in effect, and the final version of the regulations are published, designated employers will be required to comply with the relevant sectoral targets in setting the numerical goals in their employment equity plans.

This raises the question whether an employer’s current EE plan (with regards to top and senior management, as well as professionally qualified and skilled levels and people with disabilities only) will then fall on the wayside once the regulations come into effect.

Mohamed says the 2024 regulations are silent on this.

“I’m not sure why this regulation actually doesn’t have its own transitional provision to say there’s a transitional period of a year or two years to move from existing plans to the sectoral targets over a five-year period… It’s an issue that is troubling to a number of employers,” he says.

Another unresolved issue that the explanatory memorandums failed to address is how is it possible to publish regulations pursuant to an Act that has not yet been effected in law?

Pienaar says, if these regulations are to be passed, they are likely to be challenged in court later.

“It will be saying that those consultations were premature, and it could not have been done unless the Act was properly passed. And that has not happened… and there’s a potential of a challenge in terms of (when) a high penalty (is) to be imposed. That will be exactly what employers will do. They will certainly use this opportunity,” he says.

But CDH says this should not deter affected parties and stakeholders from participating in the 90-day consultation process. On the contrary, Pienaar says it is important for employers to make inputs while they can. He says that after the amendments to the EEA have been passed, they can be contested in court only.

“It (2024 draft regulations) says that it will be applied in a nuanced way. That’s what it says. But what we can tell you from experience is that once it’s done, inspectors will visit mostly larger employers, and they will apply this rigorously, and we need to ensure that once it’s finalised that there is proper compliance.”

Deadline for comment

The public has until 2 May to submit comments in writing. Comments must be sent to:

The Government Gazette containing the draft regulations on the proposed sectoral numerical targets can be accessed here.