South African fund managers and investors are becoming more despondent by the day as the divergence between South Africa’s equity market and global markets intensifies. South African stocks, particularly financials, are haemorrhaging to levels where some fund managers see them as excessively cheap.

But how cheap are South African stocks and why?

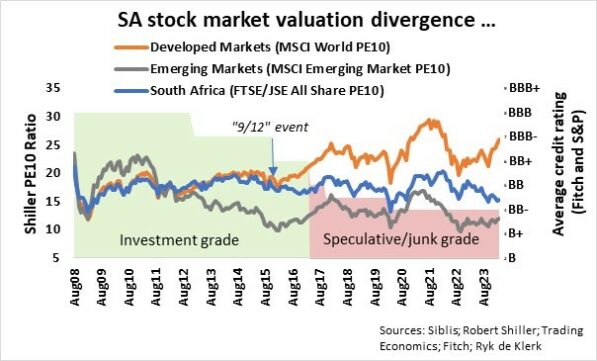

The valuation of South African equities, as measured by Professor Robert Shiller’s PE10 metric (price-to-earnings ratio based on average inflation-adjusted earnings from the previous 10 years) of the FTSE/JSE All Share Index (ALSI), narrowly tracked the PE10 of developed markets until December 2015. The “9/12” event, when former president Jacob Zuma summarily dismissed the then finance minister, Nhlanhla Nene, on 9 December 2015 and replaced him with a so-called ANC backbencher, was a watershed moment for South Africa’s financial markets.

Rating agencies Fitch and S&P slashed South Africa’s sovereign credit rating to marginal investment grade, and further downgrades to speculative, or junk, grade followed.

Over the course of the following year, the Johannesburg Stock Exchange derated to a discount of more than 20% to the PE10 of developed market equities (MSCI World Index in US dollars). It has ranged between 15% and 30% since then. Yes, the South African stock market always appeared “cheap” compared to developed markets.

Currently, the discount is more than 40%. This raises the question whether the South African stock market is “very” cheap.

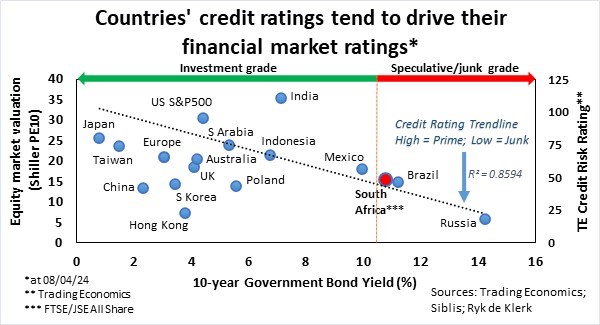

My analysis of world financial markets indicates that countries’ credit ratings and economic regions tend to drive their financial market ratings, as measured by their respective 10-year government bond yields, and stock market ratings, as measured by the PE10 metric. In the accompanying graph, I used the Trading Economic (TE) credit rating where the creditworthiness of a country ranges between one hundred (riskless) and 0 (likely to default), based on a forward looking macro-economic model. I compared the PE10 of a country against the country’s 10-year government bond yield, as well as the trendline of the TE credit ratings compared to the countries’ 10-year government bond yields.

It is evident that given the country’s TE credit rating, South Africa’s 10-year government bond yield and the PE10 of the ALSI are spot on the trendline, meaning that the markets are right in their assessment of South African financial markets. Yes, they are not cheap per se. As things stand, all other things being equal, South African financial markets will move in tandem with global financial markets.

I agree that corporate actions such as takeovers and delistings may skew my calculations because I work with the actual price and earnings yield of the ALSI instead of a summation of the free floats of individual companies and their earnings. It does give me a fair indication of trends, though.

It is also noteworthy that the presence of international companies such as Richemont and Naspers/Prosus in the ALSI skews the PE10 metric on the upside. With the PE10 of the FTSE/JSE Financial Index currently just shy of 11, I estimate that the PE10 ex-secondary listed companies could be about 11 to 12 compared to the index’s 15. It is therefore probable that the market is already pricing in a further down-rating of South Africa.

But where to from here?

The general election on 29 May will turn out to be a watershed moment – as in 1994 and in 2015 with the “9/12” event. According to https://www.matteoiacoviello.com, South Africa’s geopolitical risk is already 170% higher than it was a year ago, at a 30-year high and still climbing. The new political party uMkhonto weSizwe, backed by Zuma, has upended South Africa’s political arena.

The big question is which party or parties or groupings will be in charge after the election because this will undoubtedly have a huge and defining impact on monetary and fiscal policies going forward, as well as constitutional matters.

From the accompanying graph, if foreign investors and rating agencies view the election results positively, South Africa may find itself in Mexico’s position, with the yield on 10-year government bonds falling to 10% from about 11% currently and the ALSI’s PE10 rising by 20%, from 15 to 18 currently. Conversely, a negative view could catapult South Africa more towards Russia’s position, with bond yields rising and equity prices falling further.

I think sanity will prevail, but I expect the elevated volatility in South Africa’s financial markets to continue even after the election because it is uncertain how the losing parties will behave.

Yes, South African stocks and long-term government bonds are cheap, but not excessively so, as they come at elevated risk levels, particularly political risk.

Ryk de Klerk is an independent investment analyst.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies. The information in this article does not constitute investment or financial planning advice that is appropriate for every individual’s needs and circumstances.