Lending rates in South Africa are now at their highest levels since 2009. Businesses, consumers, and government finances are under severe strain, and some leading economists are urging the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the South African Reserve Bank to cut the repo rate by up to 2% (200 basis points).

As a layman when it comes to economics, I try to understand where the Sarb’s monetary policy came from over the past few years and where it is heading.

South Africa’s monetary policy over the past 13 years can be characterised as moving through four distinct phases.

Phase 1. Credit rating and the cost of borrowing

The first phase was highly influenced by South Africa’s credit rating and the cost of borrowing from abroad.

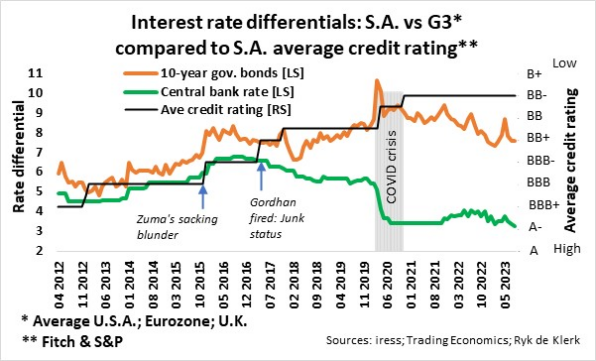

In December 2012, South Africa’s debt was downgraded on concerns about slower economic growth after mining strikes and political pressure to raise government spending.

The perceived higher risk of investing in South Africa saw the yield gap between South African 10-year government bonds and the average 10-year government bonds of the US, the United Kingdom, and the eurozone (collectively, the G3 economic zones) widening, while the rand weakened concomitantly against a basket of the G3 economic zone currencies.

Global investors punished South Africa in December 2015 when, in a matter of days, then President Jacob Zuma fired the minister of finance, appointed another, and replaced the appointee with Pravin Gordhan. The credit rating agencies downgraded South African debt again to near-junk levels, and the SA/G3 bond yield gap (SA 10-year government bonds and the average 10-year government bonds of the G3 economies) surged.

In the five years preceding the first quarter of 2017 when Gordhan was fired by Zuma resulting in the country’s credit rating cut to junk status, South Africa’s monetary policy relative to the G3 economies, as measured by the gap between the Sarb’s repo rates and the average official central bank rates in the G3 economies (the SA/G3 central bank rate gap), tended to follow the SA/G3 bond yield gap. The Sarb’s monetary policy was therefore highly influenced by the effective cost of borrowing from abroad, as it affected the external value of the rand against major currencies through capital outflows and inflation expectations.

Phase 2. Rand depreciation

The second phase of monetary policy was aimed at a gradual depreciation of the rand against major currencies while supporting economic growth.

It is evident that, after Gordhan’s firing, the widening SA/G3 bond yield gap and further downward credit ratings had scant impact on the Sarb’s monetary policy as measured by the SA/G3 central bank rate gap. The gap narrowed to about 5.4% from 6.6% due to the Sarb cutting the repo rate, while the G3 upped their rates by about 0.5%.

Despite the currency’s volatility because of domestic and global political and economic events, the Sarb’s strategy underpinned a gradual decline in the rand’s external value until the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Phase 3. Surviving the pandemic

The third phase of monetary policy was aimed at economic and social survival at the onset of the pandemic in 2020.

Globally, the onset of the pandemic in 2020 saw central banks worldwide slashing their official rates. The pandemic caused one of the largest collapses in business activity ever recorded globally. The G3 economies cut rates to 0%, while the Sarb cut the repo rate to 3.5% from 6.25%. At the same time, the rand fell by more than 15% against the G3 basket of currencies because of global risk-off investment strategies.

Phase 4. Supporting economic growth

The fourth phase of monetary policy was to support economic growth.

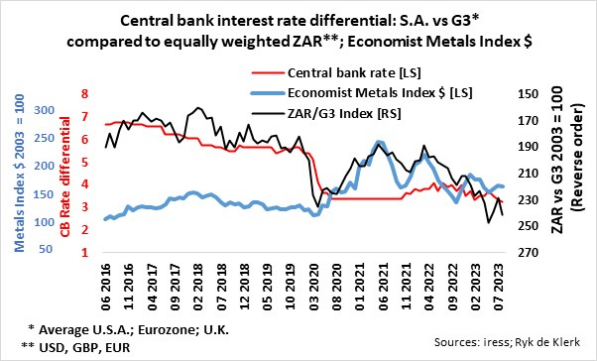

Despite the rebound in the global economy in 2021 on quantitative easing and a solid recovery in the external value of the rand on the back of pent-up demand for commodities (the Economist Metals Index in US dollars more than doubled in 2021 from 2020’s lows), the Sarb elected to maintain the gap between its repo rate and the average of the G3 economies in a very tight range of about 3.4% until November 2021, thereby supporting domestic economic growth.

Controlling inflation and supporting the rand

The current phase is aimed at bringing inflation under control and supporting the rand.

The Sarb started tightening in November 2021, slightly ahead of the aggressive quantitative tightening in the G3 economies to rein in inflation and cool off their economies. By June last year, the gap between the Sarb’s repo rate and the average central bank rate of the G3 economies widened to 4% but subsequently narrowed to 3.4% currently.

In my opinion, the decision not to return to pre-pandemic levels of a 5% plus gap between the Sarb’s repo rate and the average of the G3 economies is testimony to an effective devaluation of the rand against major currencies.

Although there is consensus that the central banks of the major developed economies and even developing countries such as South Africa and China may be done raising interest rates, I think the Sarb will continue to target a gap of 3.5% to 4% between the Sarb’s repo rate and the average of the G3 economies.

If the G3 economies’ central banks keep their rates unchanged and the Sarb cuts its repo rate by 2% (200 basis points), as suggested by some economists, the gap between the Sarb’s repo rate and the average of the G3 economies will narrow to about 1.5%.

From the accompanying graph, it is evident that such a move could lead to the rand plunging by between 12% and 15%. Yes, another devaluation of the rand, and the weaker currency will put upward pressure on inflation through more expensive imports. The Sarb’s mission should be to continue to support the rand, specifically at this stage of the global economic cycle where the world is in a growth recession and with no boon in sight for the rand, as commodity prices are under pressure.

There may be room for the Sarb’s MPC to tweak the repo rate a bit, say a cut of 0.25% (25 basis points), but I will not hold my breath for more. I personally think the Sarb will not succumb to political pressure.

Ryk de Klerk is an independent investment analyst.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and are not necessarily shared by Moonstone Information Refinery or its sister companies. The information in this article does not constitute investment or financial planning advice that is appropriate for every individual’s needs and circumstances.